Messaggio

da i-daxi » 25 ottobre 2009, 0:04

Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571

Date October 13, 1972 - December 23, 1972

Type Controlled flight into terrain

Site Remote mountainous border between Argentina and Chile

34°45′54″S 70°17′11″W / 34.765°S 70.28639°W / -34.765; -70.28639Coordinates: 34°45′54″S 70°17′11″W / 34.765°S 70.28639°W / -34.765; -70.28639

Passengers 40

Crew 5

Fatalities 29

Survivors 16

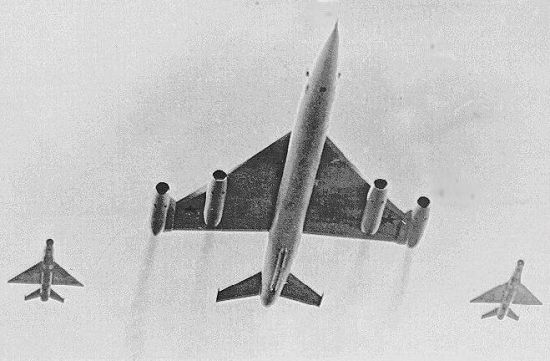

Aircraft type Fairchild FH-227D

Operator Uruguayan Air Force

Flight origin Carrasco International Airport

Stopover Mendoza International Airport

Destination Pudahuel Airport

Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571, also known as the Andes flight disaster, and in South America as Miracle in the Andes (El Milagro de los Andes) was a chartered flight carrying 45 rugby team members and associates that crashed in the Andes on October 13, 1972. The last of the 16 survivors were rescued on December 23, 1972. More than a quarter of the passengers died in the crash and several more quickly succumbed to cold and injury. Of the twenty-nine who were alive a few days after the accident, another eight were killed by an avalanche that swept over their shelter in the wreckage.

The crash survivors, thinking they would be found and rescued within days, had little food and no source of heat in the harsh climate, at over 3,600 metres (12,000 ft) altitude. Faced with starvation and radio news reports that the search for them had been abandoned, the survivors fed on the dead passengers who had been preserved in the snow. Rescuers did not learn of the survivors until 72 days after the crash when passengers Nando Parrado and Roberto Canessa, after a 12-day trek across the Andes, found a Chilean huaso, who gave them food and then alerted authorities about the existence of the other survivors.

The crash

On Friday the 13th of October, 1972, a Uruguayan Air Force twin turboprop Fairchild FH-227D was flying over the Andes carrying Stella Maris College's "Old Christians" rugby union team from Montevideo, Uruguay, to play a match in Santiago, Chile.

The trip had begun the day before, October 12, when the Fairchild departed from Carrasco International Airport, but inclement mountain weather forced an overnight stop in Mendoza. At the Fairchild's ceiling of 29,500 feet (9,000 m), the plane could not fly directly from Mendoza, over the Andes, to Santiago, in large part because of the weather. Instead, the pilots had to fly south from Mendoza parallel to the Andes, then turn west towards the mountains, fly through a low pass (Planchon), cross the mountains and emerge on the Chilean side of the Andes south of Curico before finally turning north and initiating descent to Santiago after passing Curico. After resuming the flight on the afternoon of October 13, the plane was soon flying through the pass in the mountains. The pilot then notified air controllers in Santiago that he was over Curicó, Chile, and was cleared to descend. This would prove to be a fatal error. Since the pass was covered by the clouds, the pilots had to rely on the usual time required to cross the pass (dead reckoning). However, they failed to take into account strong headwinds that ultimately slowed the plane and increased the time required to complete the crossing: they were not as far west as they thought they were. As a result, the turn and descent were initiated too soon, before the plane had passed through the mountains, leading to a controlled flight into terrain.

Dipping into the cloud cover while still over the mountains, the Fairchild soon crashed on an unnamed peak (later called Cerro Seler, also known as Glaciar de las Lágrimas or Glacier of Tears), located between Cerro Sosneado and Volcán Tinguiririca, straddling the remote mountainous border between Chile and Argentina. The plane clipped the peak at 4,200 metres (14,000 ft), neatly severing the right wing, which was thrown back with such a force that it cut off the vertical stabilizer, leaving a gaping hole in the rear of the fuselage. The plane then clipped a second peak which severed the left wing and left the plane as just a fuselage flying through the air. One of the propellers sliced through the fuselage as the wing it was attached to was severed. The fuselage hit the ground and slid down a steep mountain slope before finally coming to rest in a snow bank. The location of the crash site is 34°45′54″S 70°17′11″W / 34.765°S 70.28639°W / -34.765; -70.28639Coordinates: 34°45′54″S 70°17′11″W / 34.765°S 70.28639°W / -34.765; -70.28639, in the Argentine municipality of Malargüe (Malargüe Department, Mendoza Province).

Early days

Survivors amongst the wreckage.Of the 45 people on the plane, 12 died in the crash or shortly thereafter; another 5 had died by the next morning, and one more succumbed to injuries on the eighth day. The remaining 27 faced hard survival issues high in the freezing mountains. Many had suffered injuries from the crash including broken legs from the aircraft's seats piling together. The survivors lacked equipment such as cold-weather clothing and footwear suitable for the area, mountaineering goggles to prevent snow blindness (although one of the eventual survivors, 24-year-old Adolfo "Fito" Strauch, devised a couple of sunglasses by using the sun visors in the pilot's cabin which did help protect their eyes from the sun). Most gravely, they lacked any kind of medical supplies, leaving the two first year medical students on board who had survived the crash to improvise splints and braces with salvaged parts of what remained of the aircraft.

The search

Search parties from three countries looked for the missing plane. However, since the plane was white, it blended in with the snow making it virtually impossible to see from the sky. The search was cancelled after 8 days. The survivors of the crash had found a small transistor radio on the plane and Roy Harley first heard the news that the search was cancelled on their eleventh day on the mountain. Piers Paul Read in Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors (a text based upon interviews with the survivors) described the moments after this discovery:

“ The others who had clustered around Roy, upon hearing the news, began to sob and pray, all except Parrado, who looked calmly up the mountains which rose to the west. Gustavo [Coco] Nicolich came out of the plane and, seeing their faces, knew what they had heard… [Nicolich] climbed through the hole in the wall of suitcases and rugby shirts, crouched at the mouth of the dim tunnel, and looked at the mournful faces which were turned towards him. 'Hey boys,' he shouted, 'there's some good news! We just heard on the radio. They've called off the search.' Inside the crowded plane there was silence. As the hopelessness of their predicament enveloped them, they wept. 'Why the hell is that good news?' Paez shouted angrily at Nicolich. 'Because it means,' [Nicolich] said, 'that we're going to get out of here on our own.' The courage of this one boy prevented a flood of total despair. ”

Cannibalism

The survivors had a small amount of food: a few chocolate bars, other assorted snacks, and several bottles of wine. During the days following the crash they divided out this food in very small amounts so as not to exhaust their meager supply. Fito also devised a way to melt snow into water by using metal from the seats and placing snow on it. The snow then melted in the sun and dripped into empty wine bottles.

Even with this strict rationing, their food stock dwindled quickly. Furthermore, there was no natural vegetation or animals on the snow-covered mountain. The group thus survived by collectively making a decision to eat flesh from the bodies of their dead comrades. This decision was not taken lightly, as most were classmates or close friends. In his 2006 book, Miracle in the Andes: 72 Days on the Mountain and My Long Trek Home, Nando Parrado comments on this decision:

“ At high altitude, the body's caloric needs are astronomical … we were starving in earnest, with no hope of finding food, but our hunger soon grew so voracious that we searched anyway … again and again we scoured the fuselage in search of crumbs and morsels. We tried to eat strips of leather torn from pieces of luggage, though we knew that the chemicals they'd been treated with would do us more harm than good. We ripped open seat cushions hoping to find straw, but found only inedible upholstery foam… Again and again I came to the same conclusion: unless we wanted to eat the clothes we were wearing, there was nothing here but aluminium, plastic, ice, and rock.”

All of the passengers were Roman Catholic, a point which was emphasized by Piers Paul Read in Alive. According to Read, some equated the act of cannibalism to the ritual of Holy Communion. Others initially had reservations, though after realizing that it was their only means of staying alive, changed their minds a few days later.

Avalanche

Eight of the initial survivors subsequently died on the morning of October 29 when an avalanche cascaded down on them as they slept in the fuselage. For three days they survived in an appallingly confined space since the plane was buried under several feet of snow. Nando Parrado was able to poke a hole in the roof of the fuselage with a metal pole, providing ventilation and possibly saving them all from suffocation.

Hard decisions

Before the avalanche, a few of the survivors became insistent that their only means of survival would be to climb over the mountains themselves and search for help. Because of the co-pilot's assertion that the plane had passed Curico, the group assumed that the Chilean countryside was just a few miles away to the west. In actuality, the plane had crashed inside Argentina and just a few miles west of an abandoned hotel named the Hotel Termas Sosneado. Several brief expeditions were made in the immediate vicinity of the plane in the first few weeks after the crash, but the expeditionaries found that a combination of altitude sickness, dehydration, snow blindness, undernourishment and the extreme cold of the nights made climbing any significant distance an impossible task. Therefore it was decided that a group of expeditionaries would be chosen, and then allocated the most rations of food and the warmest of clothes, and spared the daily manual labor around the crash site that was essential for the group's survival, so that they might build their strength. Although several survivors were determined to be on the expedition team no matter what, including Parrado and one of the two medical students, Roberto Canessa, others were less willing or unsure of their ability to withstand such a physically exhausting ordeal. Three of the survivors ultimately undertook a one-day trial climb to test their willingness and ability to withstand the challenges of climbing, after which only Antonio "Tintin" Vizintín was declared fit enough to join the other two.

At Canessa's urging, the expeditionaries waited nearly seven weeks, to allow for the arrival of spring, and with it warmer temperatures. Although the expeditionaries were hoping to get to Chile, a large mountain lay due west of the crash site, blocking any effort made to walk in that direction. Therefore the expeditionaries initially headed east, hoping that at some point the valley that they were in would do a U-turn and allow them to start walking west. After several hours of walking east, the trio unexpectedly found the tail section of the plane, which was still largely intact. Within and surrounding the tail were numerous suitcases that had belonged to the passengers, containing cigarettes, candy, clean clothing and even some comic books. The group decided to camp there that night inside the tail section, and continue east the next morning. However, on the second night of the expedition, which was their first night sleeping outside exposed to the elements, the group nearly froze to death. After some debate the next morning, they decided that it would be wiser to return to the tail, remove the plane's batteries and bring them back to the fuselage so that they might power up the radio and make an SOS call to Santiago for help.

Radio

Upon returning to the tail, the trio found that the batteries were too heavy to take back to the fuselage, which lay uphill from the tail section, and they decided instead that the most appropriate course of action would be to return to the fuselage and disconnect the radio system from the plane's electrical mainframe, take it back to the tail, connect it to the batteries, and call for help from there. One of the other team members, Roy Harley, was an amateur electronics enthusiast, and they recruited his help in this endeavor. Unbeknownst to any of the team members, though, was the fact that the plane's electrical system used AC, while the batteries in the tail naturally produced DC, making the plan futile from the beginning. After several days of trying to make the radio work back at the tail, the expeditionaries finally gave up, returning to the fuselage with the knowledge that they would in fact have to climb out of the mountains if they were to stand any hope of being rescued.

The sleeping bag

It was now apparent that the only way out was to climb over the mountains to the west. However, they also realized that unless they found a way to survive the freezing temperature of the nights, a trek was impossible. It was at this point that the idea for a sleeping bag was raised.

In his book, Miracle in the Andes: 72 Days on the Mountain and My Long Trek Home, Nando Parrado would comment thirty-four years later upon the making of the sleeping bag:

“ The second challenge would be to protect ourselves from exposure, especially after sundown. At this time of year we could expect daytime temperatures well above freezing, but the nights were still cold enough to kill us, and we knew now that we couldn't expect to find shelter on the open slopes. We needed a way to survive the long nights without freezing, and the quilted batts of insulation we'd taken from the tail section gave us our solution … as we brainstormed about the trip, we realized we could sew the patches together to create a large warm quilt. Then we realized that by folding the quilt in half and stitching the seams together, we could create an insulated sleeping bag large enough for all three expeditionaries to sleep in. With the warmth of three bodies trapped by the insulating cloth, we might be able to weather the coldest nights.

Carlitos took on the challenge. His mother had taught him to sew when he was a boy, and with the needles and thread from the sewing kit found in his mother's cosmetic case, he began to work … to speed the progress, Carlitos taught others to sew, and we all took our turns… C, Coche, Gustavo [Zerbino], and Fito turned out to be our best and fastest tailors".

After the sleeping bag was completed and another survivor, Numa Turcatti, died from his injuries, the hesitant Canessa was finally persuaded to set out, and the three expeditionaries took to the mountain on December 12.

December 12

On 12 December, 1972, some two months after the crash, Parrado, Canessa and Vizintín began their trek up the mountain. Parrado took the lead, and often had to be called to slow down, although the trek up the hill against gravity and in low-oxygen was difficult for all of them. Although it was still bitterly cold, the sleeping bag allowed them to live through the nights.

On the third day of the trek, Parrado reached the top of the mountain before the other two expeditionaries. What he saw literally took his breath away. Stretched before him as far as the eye could see were more mountains. In fact he had just climbed one of the mountains (as high as 4,800 metres (16,000 ft)) which forms the border between Argentina and Chile, meaning that they were still tens of kilometers from the red valley of Chile. However, after spying a small "Y" in the distance, he gauged that a way out of the mountains must lie beyond, and refused to give up hope. Knowing that the hike would take more energy than they'd originally planned for, Parrado and Canessa sent Vizintín back to the crash site, as they were rapidly running out of rations. Since the return was entirely downhill, it only took him one hour to get back to the fuselage on a sled made from broken parts of the plane.

Finding help

Parrado and Canessa hiked for several more days. First, they were able to actually reach the narrow valley that Parrado had seen on the top of the mountain, where they found the bed of Rio Azufre; then they followed the river and finally they reached the end of the snowline and, gradually, more and more signs of human presence, first some signs of camping and finally, on the ninth day, some cows. When they rested that evening, they were very tired and Canessa seemed unable to proceed further. As Parrado was gathering wood to build a fire, Canessa noticed what looked like a man on a horse at the other side of the river, and yelled at the near-sighted Parrado to run down to the banks. At first it seemed that Canessa had been imagining the man on the horse, but eventually they saw three men on horseback. Divided by a river, Nando and Canessa tried to convey their situation to which one of them, a Chilean Huaso named Sergio Catalan, shouted "tomorrow." They knew at this point they would be saved and settled to sleep by the river.

During the evening dinner, Sergio Catalan discussed what he had seen with the other huasos who were staying at the time in a little summer ranch called Los Maitenes. Someone mentioned that several weeks before the father of Carlos Paez, who was desperately searching for any possible news about the plane, had asked them about the Andes crash; however, the huasos could not imagine that someone could still be alive. The next day Catalan took some loaves of bread and went back to the river bank, where he found the two men who were still on the other side of the river, on their knees and asking for help. Catalan threw them the bread loaves, which they immediately ate and following Parrado's gestures, a pen and paper to write a note, addressed in red lipstick, telling the huasos about the plane crash and asking for help; then he tied the paper to a rock and threw it back to Catalan, who read it and gave the boys the sign to have understood.

Catalan rode on horseback for many hours westwards to bring help. During the trip he saw another huaso on the south side of Rio Azufre and asked him to reach the boys and to bring them to Los Maitenes. Instead, he followed the river till the cross with Rio Tinguiririca, where, after passing a bridge he was able to reach the narrow route that linked the village of Puente Negro to the holiday resort of Termas del Flaco. Here he was able to stop a truck and reach the police station at Puente Negro, where the news was finally dispatched to the Army command in San Fernando and then to Santiago. Meanwhile, Parrado and Canessa were rescued and they reached Los Maitenes, where they were fed and allowed to rest.

The following day in the morning the rescue expedition left Santiago and, after a stop in San Fernando, moved eastwards. The two helicopters had to fly in the fog and reached a place near Los Maitenes just when Parrado and Canessa were passing there on horseback while going to Puente Negro. Nando Parrado was recruited to fly back to the mountain in order to guide the helicopters to the remaining survivors. The news that people had survived the October 13 crash of Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571 had also leaked to the international press and a flood of reporters also began to appear along the narrow route from Puente Negro to Termas del Flaco. The reporters hoped to be able to see and interview Parrado and Canessa about the crash and the following days.

Parrado and Canessa with Chilean Huaso Sergio Catalan[edit] The mountain rescue

In the morning of the day when the rescue started, those remaining at the crash site heard on their radio that Parrado and Canessa had been successful in finding help and that afternoon, 22 December, 1972, two helicopters carrying search and rescue climbers arrived. However, the expedition (with Parrado onboard) was not able to reach the crash site until the afternoon, when it is very difficult to fly in the Andes. In fact the weather was very bad and the two helicopters were able to take only half of the survivors. They departed, leaving the rescue team and remaining survivors at the crash site to once again sleep in the fuselage, until a second expedition with helicopters could arrive the following morning. The second expedition arrived at daybreak on 23 December and all sixteen survivors were rescued. All of the survivors were taken to hospitals in Santiago and treated for altitude sickness, dehydration, frostbite, broken bones, scurvy and malnutrition.

Timeline

October 1972

October 12 (Thu)

Crew 5, Passengers 40. (alive: 45)

October 13 (Fri)

5 people missing, 12 people dead. (dead: 12, missing: 5, alive: 28)

October 21 (Sat)

Susana "Susy" Parrado found dead. (dead: 13, missing: 5, alive: 27)

October 24 (Tue)

missing 5 people found dead. (dead: 18, alive: 27)

October 29 (Sun)

8 people killed in an avalanche. (dead: 26, alive: 19)

November 1972

November 15 (Wed)

Arturo Nogueira, found dead. (dead: 27, alive: 18)

November 18 (Sat)

Rafael Echavarren, found dead. (dead: 28, alive: 17)

December 1972

December 11 (Mon)

Numa Turcatti, found dead. (dead: 29, alive: 16)

December 20 (Wed)

Parrado and Canessa encounter Sergio Catalan.

December 21 (Thu)

Parrado and Canessa rescued.

December 22 (Fri)

6 people rescued.

December 23 (Sat)

8 people rescued. 16 people alive.

December 26 (Tue)

Front page of the Santiago newspaper, "El Mercurio", reports that all survivors resorted to cannibalism.

Passenger list

Crew

Colonel Julio Ferradas, Pilot,

Lieutenant Colonel Dante Lagurara, Co-Pilot,

Lieutenant Ramon Martínez,

Corporal Carlos Roque,

Corporal Ovidio Joaquin Ramírez.

Passengers

Francisco Abal

Jose Pedro Algorta

Roberto Canessa

Gaston Costemalle

Alfredo Delgado

Rafael Echavarren

Daniel Fernández

Roberto Francois

Roy Harley

Alexis Hounié

Jose Luis Inciarte

Guido Magri

Alvaro Mangino

Felipe Maquirriain

Graciela Augusto Gumila de Mariani

Julio Martínez-Lamas

Daniel Maspons

Juan Carlos Menéndez

Javier Methol

Liliana Navarro Petraglia de Methol

Dr. Francisco Nicola

Esther Horta Pérez de Nicola

Gustavo Nicolich

Arturo Nogueira

Carlos Páez Rodriguez

Eugenia Dolgay Diedug de Parrado

Fernando Parrado

Susana Parrado

Marcelo Perez

Enrique Platero

Ramón Sabella

Daniel Shaw

Adolfo Strauch

Eduardo Strauch

Diego Storm

Numa Turcatti

Carlos Valeta

Fernando Vázquez

Antonio Vizintín

Gustavo Zerbino

Aftermath

When first rescued, the survivors initially explained that they had eaten some cheese they had carried with them, planning to discuss the details in private with their families. However, they were pushed into the public eye when photos were leaked to the press and sensational, unauthorized articles were published.

The survivors held a press conference on December 28 at Stella Maris College, where they recounted the events of the past 72 days (over the years, they would also participate in the publication of two books, two films, and an official website about the event).

The rescuers later returned to the crash site and buried the bodies of the deceased under a pile of stones a half mile from the site. The grave was commemorated by an iron cross erected from the center of the stone pile. What remained of the fuselage was incinerated to thwart curiosity seekers.

View of the Crash Site Memorial - February 2006. Official website (2002)

In 2002, on the occasion of the 30th anniversary of the event, an official website was created for the survivors. The website, entitled Viven! El Accidente de Los Andes is available in both Spanish and English.

Books

Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors (1974)

The first book, Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors, (published two years after their rescue) was written by Piers Paul Read who interviewed the survivors and their families. It was a critical success and remains a highly popular work of non-fiction. In the opening of the book, the survivors explain why they wanted it to be written:

“ We decided that this book should be written and the truth known because of the many rumors about what happened in the cordillera. We dedicate this story of our suffering and solidarity to those friends who died and to their parents who, at the time when we most needed it, received us with love and understanding. ”

A reprint was published in 2005 by Harper. It was re-titled: Alive: Sixteen Men, Seventy-two Days, and Insurmountable Odds—The Classic Adventure of Survival in the Andes and includes a revised introduction as well as interviews with Piers Paul Read, Coche Inciarte, and Álvaro Mangino.

Miracle in the Andes (2006)

Thirty-four years after the rescue, Nando Parrado published the book Miracle in the Andes: 72 Days on the Mountain and My Long Trek Home (with Vince Rause), which has received positive reviews. In this text, Parrado also touches upon public reaction to this event:

“ In fact, our survival had become a matter of national pride. Our ordeal was being celebrated as a glorious adventure… I didn't know how to explain to them that there was no glory in those mountains. It was all ugliness and fear and desperation, and the obscenity of watching so many innocent people die. I was also shaken by the sensationalism with which many in the press covered the matter of what we had eaten to survive. Shortly after our rescue, officials of the Catholic Church announced that according to church doctrine we had committed no sin by eating the flesh of the dead. As Roberto had argued on the mountain, they told the world that the sin would have been to allow ourselves to die. More satisfying for me was the fact that many of the parents of the boys who died had publicly expressed their support for us, telling the world they understood and accepted what we had done to survive … despite these gestures, many news reports focused on the matter of our diet, in reckless and exploitive ways. Some newspapers ran lurid headlines above grisly front-page photos. (247–8) ”

Film and television

Stranded: I Have Come from a Plane That Crashed on the Mountains (2007)

Stranded: I Have Come from a Plane That Crashed on the Mountains, written and directed by Gonzalo Arijón, is a documentary film interlaced with dramatised scenes. In the film, all of the survivors are interviewed, as are some of their family members and the people involved with the rescue operation. Additionally, an expedition in which the survivors return to the crash site is documented. The film was first shown at the 2007 International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam, The Netherlands and received the Joris Ivens Award.

This film appeared on PBS Independent Lens as STRANDED: The Andes Plane Crash Survivors in May 2009.

Trapped: Alive in the Andes (2007)

Trapped: Alive in the Andes is an episode from season one of the National Geographic Channel documentary television series Trapped. The series was dedicated to examining the stories of various accidents which left survivors trapped in their situation for a period of time. The episode Trapped: Alive in the Andes was aired November 7, 2007.

Alive: The Miracle of the Andes (1993)

The film Alive received mixed reviews. It was directed by Frank Marshall and is based upon the book Alive: The Story of the Andes Survivors by Piers Paul Read. It stars Ethan Hawke and is narrated by John Malkovich. Nando Parrado served as a technical adviser to the film. Carlitos Páez (see: Casapueblo) and Ramon "Moncho" Sabella also visited the recreated fuselage during the shooting of the movie to aid with the historical accuracy of the set and to instruct the actors on how the events actually unfolded.

Alive: 20 Years Later (1993)

Alive: 20 Years Later is a documentary film which was produced, directed and written by Jill Fullerton-Smith and narrated by Martin Sheen. It explores the lives of the survivors twenty years after the crash. It also discusses their participation in the production of Alive: The Miracle of the Andes.

Supervivientes de los Andes (1976)

This was a Mexican production directed by René Cardona, Jr.,[10] based on the unauthorized 1973 book, Survive by Clay Blair.

-

Allegati

-

- Fairchild FH-227 of Fuerza Aerea Uruguaya, flight 571 Photo taken in the summer 1972.

-

- Survivors amongst the wreckage.

- 000000000000000.jpg (26.91 KiB) Visto 30890 volte

-

- Parrado and Canessa with Chilean Huaso Sergio Catalan

-

- View of the Crash Site Memorial - February 2006